As with all natural tastes, the flavor of food is dependent on the plant secondary compounds within it, the quality of its growing environment and the time of harvest. The harsh dry climate of Cyprus in Greece, for example, produces the most outstanding rosemary. This wonderfully aromatic herb needs to work hard to grow here, but with that hard work, it also produces a higher volatile oil content – which gives the plant its unique smell and taste.

What I was most shocked about, concerning the umami (savory) flavor was that it was with us all along. Yet when most of us bite into a tomato or cheese, the flavor is bland. Most tomatoes on the market taste like nothing, when you grow one from your garden or get one from the farmers market, it is amazing how they should taste. Cheese is another culprit of tasting like nothing. Parmigiano Reggiano is a work of art, and it can only be made in one place, Parma, Italy. The local environment (the climate, geography, soil quality) is particular to that place, as is the aging of the cheese. Kraft has its own Parmigiano cheese, which they now name 100% Grated Parmesan Cheese, with the 100% directed at the grating process and not the fact that there is 100% real cheese in the mixture, the taste is not there either. True Parmigiano Reggiano also contains the savory umami flavor.

Umami Taste – The Fifth Basic Taste

The savoriness of umami promotes salivation, aids in digestion and when consumed in whole food form is incredibly healing to the body. Three substances in food give the umami flavor to the pallet; glutamic acid (glutamate), 5′-inosinate, and 5′-guanylate. Glutamic acid is an amino acid, and it is on this substance that MSG was inspired, 5′-inosinate and 5′- guanylate are both 5′-nucleotides. The three substances have a strong synergy together, combining in different ways on umami receptors to stimulate the brain and our senses (Kurihara, K., 2015).

5′- inosinate

This nucleotide is created during the decomposition of animal protein (example bonito). As ATP breaks down it turns into AMP, which over time develops into 5′-inosinate, it is this nucleotide that gives the animal protein its delicious taste. It is made artificially into a chemical flavoring – food may taste delicious but it may not be truly healthy (Kurihara, K., 2015).

5′-guanylate

This nucleotide is produced during the decomposition of ribonucleic acid and its contact with ribonuclease which results in 5′-guanylate. 5’guanylate is found in raw and dried mushrooms, with higher content in dried mushrooms such as shitake as it cells have broken down releasing the ribonuclease (Kurihara, K., 2015).

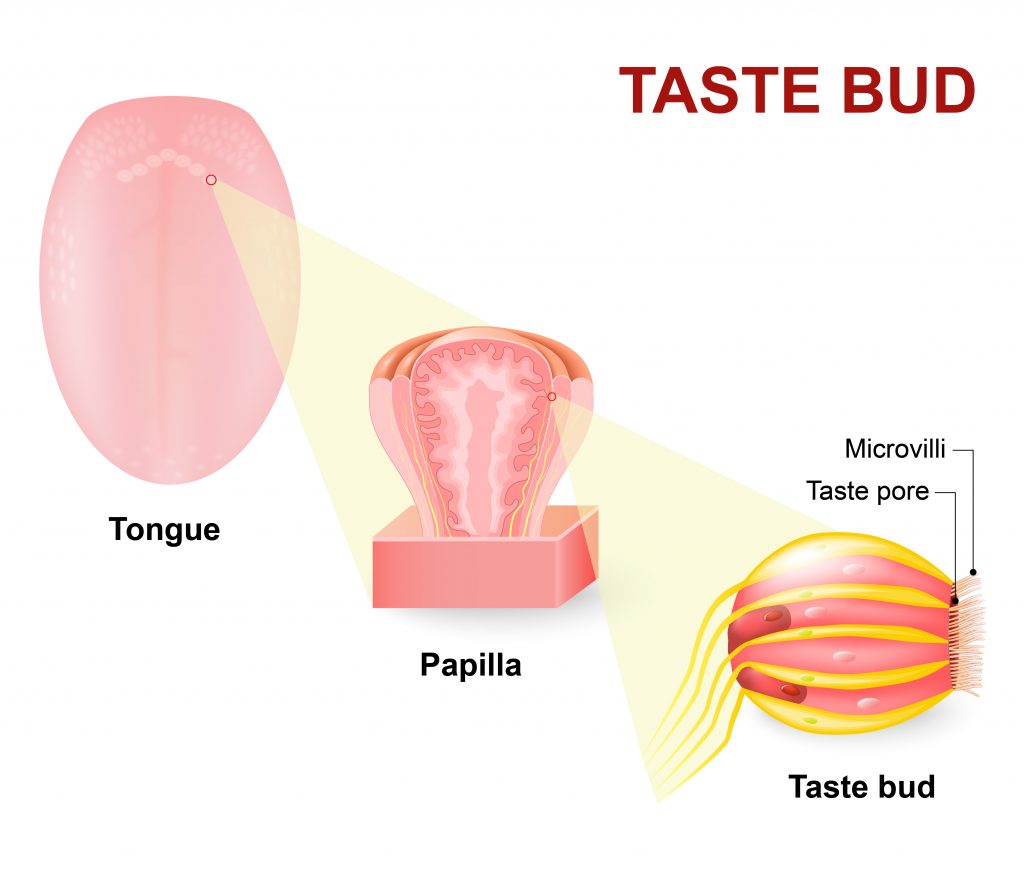

In the early 2000 umami receptors were finally discovered. Although the concept of a fifth taste was acknowledged in the late 1970’s early 1980’s, it was not until the 2000’s that the receptors for umami were discovered on the tongue. There are three umami receptors; T1R1 + T1R3, mGluR4, and mGluR1 (Kurihara, K., 2015). The umami receptors (taste buds) are located in specialized neuroepithelial cells that are located in the stratified epithelia of the mouth. The tip of the taste bug is a taste pore, this is the bit that makes a connection with both saliva and food (Chaudhari, N., et al., 2009).

T1R1 + T1R3

This heterodimeric complex of T1R1 + T1T3 amino acid receptors are stimulated when the synergy between 5′-inosinate and glutamic acid /glutamate is felt.

MG1u4 and MG1uR1

These are both metabolic glutamate receptors. They exist on the taste buds as a receptor for glutamic acid/glutamate.

These receptors are also located in the stomach and the intestinal wall. They stimulate the brain and have an effect on the body’s thermoregulation (maintaining an appropriate core temperature) as well as homeostatic control of energy balance (an energy flow of food intake and energy output) (Kurihara, K., 2015).

Umami – Glutamic Acid

Glutamic acid is the main component in all umami foods. It is an excitatory amino acid, though non-essential, in today’s society it can be very beneficial and healing to include this in one’s diet. It is called an excitatory amino acid because it aids in stimulating the nervous system, however, depending on the pathway of conversion in the body, it can also be relaxing. Glutamic acid can become either l-glutamine or GABA.

L-Glutamine

Made within the body, but in the modern world, it can be in short demand. L-Glutamine is very healing for the lining of the digestive system, primarily the small intestine and has been shown to reduce cravings for sugars and carbohydrates. It aids in strengthening the migratory motor complex, the muscles that aid in pushing our food through the gut as well as cleaning our digestive system out ensuring that no bad bacteria build-up (Haas, E.M., 2006). The Standard American Diet, consuming allergens or intolerant foods, as well as a high-stress lifestyle, can result in the lining and motility of the digestive system to become damaged. Moreover, though this amino acid is produced by the body (that is why it is called non-essential as the body should be able to make it) if the precursors to l-glutamine are not present or if there is an issue in its cycle it can result in a depletion within the body, leading to more issues with body system strength and health.

GABA

GABA is a nervine relaxant, aiding in calming stress and anxiety, as well as being beneficial against high blood pressure and possibly epilepsy (Haas, E., 2006). GABA is manufactured in the brain, and supplementation for it needs to be done through precursors as GABA molecules are too large to pass through the blood-brain barrier.

Umami History

The term umami was first coined in 1908 by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, upon his discovery of glutamic acid in kombu (Ninomiya, K., 2015). The word umami means “Essence of Taste” in Japanese and is derived from two characters ‘umai’ meaning delicious and ‘mi’ meaning the essence or taste (Mouritsen, O.G., et al., 2012).

In 1909, Ikeda paired up with Suzuki an iodine manufacturer and developed MSG (monosodium glutamate) as a new umami seasoning that could be used to enhance the flavor of all food with just a sprinkle. This, as well as manufactured Vanillin (not real vanilla), was not a natural derivative of glutamate (Ninomiya, K., 2015). Wheat protein also contains a large amount of glutamic acid, the company used that as their MSG base and added iodized salt as it allowed them the ability to mass-produce. The vision that Ikeda had was to provide bland food with the ‘umami’ flavor and food with more nutrients, however, the concentrated form of MSG that the company produced if often overused and the health benefits are lost, as they do not contain the other beneficial compounds of a whole food or umami dashi.

In 1913, Shintaro Kodama discovered another component in food that also gave the umami flavor. It was 5′- inosinate, which was found in fermented katsuobushi, so dried bonito flakes (Ninomiya, K., 2015). Bonito also contains levels of the glutamic acid and it is used as part of dashi broth as well as other Japanese dishes.

In 1957, Akira Kuninaka, a Japanese scientist discovered (after he isolating 5′-guanylate from Shitakes) that guanylate in dried Shitake Mushrooms and inosinate from fermented Katsubushi had a synergistic relation to glutamate in dried fermented konbu. We know now that they would bind together on the umami receptors of the tongue and enhance the umami flavor (Mouritsen, O.G., et al., 2012) (Ninomiya, K., 2015).

In 1979, Shizuko Yamaguchi headed a presentation at the “The Umami Taste”, that solidified the concept of umami on a global scale. This lead to the first “International Symposium on Umami” in 1985 which was held in Hawaii. Progress and awareness for the fifth basic taste continued when in 2002, the umami taste receptor on the tongue was discovered, establishing that umami (savory) was a fifth basic taste (Ninomiya, K., 2015).

Umami Foods

Kombu

Kombu, an alga of the order Laminariales, grows to be upwards of several meters and has a width that ranges from 10-30 cm. It is grown in the Sea of Japan (which lies between China and Japan). Kombu contains a large amount of glutamic acid, which is a non-essential amino acid (the building block to l-glutamine which is made by the body).

After it is harvested it is sun-dried. The highest quality of kombu, which also provides the best quality of umami is aged in cellars for as little as a year to as long as ten years, with the most common aging period being 2 years. The aging or fermenting process is important as it produces a milder flavor and the umami becomes more pronounced (Mouritsen, O.G., et al., 2012).

When shopping for kombu, you may come upon dried kombu that has a white layer on its surface, this is a natural occurrence. It occurs when the free monosodium glutamate binds with salt and mannitol (sweet sugar alcohol) – providing an intense umami taste (as the aging process also allows for more salt and glutamate to be given off). When soaked in water the combination will dissolve and make a delicious dashi broth (ibid).

The best kombu to look for is the one that carries the most glutamic acid (glutamate) in it. The variety makonbu contains approximately 3.2 g per 100g, along with rausu-kombu and rishiri-kombu it is the preferred konbu for making dashi. Hidaka-kombu contains the lowest level of glutamate at 1.3g per 100g. When made into dashi, rausu-kombu dashi will contain 145mg of glutamate per liter (ibid).

Katsuobushi – Bonito

This fish is a member of the Scombrid family (having a relation to the Mackerel and Tuna) it is also known as the Skipjack tuna (Davidson, A., 1999). You will often find this variety in canned tuna, however, in Japan they turn it into the hardest food on the planet – Katsuobushi. This wonderfully flavored fermented fish has a history that dates back to the mid-Edo Period. In 1674 the fish was first simply smoked dried to enhance the flavor, and the mold fermentation component to further enhance the flavor was implemented in 1770.

Katshubushi is the component of the most popular type of Japanese dashi, awase dashi, though Ichiban and niban dashi also incorporate bonito flakes. Higher-end restaurants in Japan (Ryotei), use tuna bushi instead of katsu bushi as it is a more highly prized fish in Japan. Katshubushi is an important part of Japanese gastronomy. Its fermentation brings forth a strong umami flavor (Fujita, C., 2009). Bonito flakes contain approximately 30-40 mg of glutamate per 100g serving and 400-700mg/100g serving of inosinate (Umami info, 2017).

Shiitake Mushrooms

Shiitake (aka the elixir of life) or Lentinus edodes grows naturally on rotting logs (primarily of oak trees). Native to China and Japan, cultivation has now begun in Europe and North America. Shiitake mushrooms have many health benefits, such as boosting the immune system, promoting a healthy digestive system and balancing cholesterol levels within the body. Shiitake mushrooms have a very bold and strong flavor, drying them gives the much milder taste but stronger umami as the glutamate levels increase as a result of cell death (Davidoson, A., 2011).

Dried Shiitake Mushrooms contain 1060 mg / 100g serving, comparable to fresh shiitake mushrooms that contain only 70 mg/100g serving (Umami Info, 2017).

Dulse

It is the most widely used edible red seaweed and the most delicious. It is native to the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is traditionally used in Ireland/Scottland/Iceland, though it is in Ireland where it has the longest culinary history and where it has its name derived, used as a topping for potatoes or boiled milk (Davidson, A., 2011).

This thin, red and purple intertidal seaweed grows to be between 1/2 meter in length. When made into dashi, dulse dashi will contain 40 mg of glutamate per liter (Mouritsen, O.G., et al., 2012).

Many types of foods contain natural free form glutamate which brings about the umami flavor.

- Marmite

- Fish Sauce

- Parmigiano Reggiano

- Blue Cheese

- Asparagus

- Tomatoes

- Sun-dried Tomatoes

- Anchovies

- Soy Sauce

- Prosciutto di Parma

- Heritage Chickens

- Grass-Fed Beef

- Kimchi

- Ginger

- Potatoes

- Corn

- Green Peas

- Lotus Root

- Garlic

- Wakame

- Small Dried Sardines

- Large Sardines

- Clams

- Scallops

- Mussels

- Shrimp (fresh not frozen)

- Sea Urchin

- Squid

- Oysters

- Octopus

- Hamachi

- Sardines

- Tuna

- Sea Bream

- Horse Mackerel

- Japanese Spanish Mackerel

- Cod

(Mouritsen, O.G., et al., 2012) (Ninomiya, K., 2015) (Umami Info, 2017)

Benefits of Umami

Umami may simply be a taste that your brain recognizes, but when choosing whole foods that provide a lot of savory umami, you can be sure that you are eating something very healthy. Miso soup in Japan it the traditional soup, served most commonly once a day. In a 2012 Japanese study (Kawai, M., et al) of elderly living in nursing homes who were served miso once daily were found to do better with miso made traditionally. The use of MSG instead of making dashi (Japanese Umami soup base) from scratch resulted in them eating more. MSG, like any chemical flavoring, will almost always leave the individual wanting more (the Dorito effect). As we age we tend to require less food. This does not mean we should feed elderly individuals foods that will lead to craving more food, we should instead be providing nutrient-dense food, that will keep them full, leave their bodies strong, stimulate brain and heart health as well as reducing inflammation – real food can do all of that!

Umami and MSG

You most likely by now have heard of or perhaps experienced the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”. You may come upon restaurants with signs in their window saying that they no longer use MSG. Perhaps they use MSG is a patented product name, they very well may not be using it, though they could be using another product that provided the safely manufactured glutamate for the umami flavor. Other restaurants claim nothing, just because it is pricey doesn’t mean they can’t swindle their customers – think about all that truffle oil, fake Kobe beef, fake olive oil, etc. classy places sell as the real deal. What exactly is the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrom” and why is MSG not beneficial but Umami is?

Chinese Restaurant Syndrom

Known also as monosodium glutamate symptom complex, this issue includes the following symptoms; flushing of the body, headaches, sweating, pressure sensation on the face or within the mouth, etc. The glutamate in MSG stimulates the nervous system, in some individuals, even with small doses of MSG (1/8 tsp per serving or >3 g) this may produce the sensation of numbness or tingling (Haas, M., 2006).

Chinese restaurant syndrome is either a neurotoxicity issue or an allergic issue. Neurotoxicity is associated with high doses of MSG (which is very absorbable as it is already brown down so the digestive system can simply absorb it without exerting any work) (eds. Metcalfe, D.D., et al., 2011) – though when consumed naturally from a diet of whole foods, glutamate is not used as a precursor in the brain, not do the receptors of on the tongue correspond with the glutamate receptors of the brain (Chaudhari, N, et al., 2009).

Though no studies have shown that MSG as a flavor additive is harmful to the body, it has since the mid-1900’s been used within more processed foods (canned goods, frozen dinner meals, fast food, etc). Moreover, it is artificially made from wheat protein, a food item that a lot of individuals are having an allergy or intolerance too. The dosage of the MSG is also dependent on the manufacturer, as there is no recommended daily intake of glutamate (as it is an unessential amino acid) the amount of MSG is a single serving can be far more than 3g! This in itself, can result in discomfort for most individuals.

References

Chaudhari, N., Pereira, E., & Roper, S. D. (2009). Taste receptors for umami: the case for multiple receptors. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(3), 738S–742S.

Davidson, A. (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press: New York.

Fujita, C. (2009). Dried Bonito. The Tokyo Foundation.

eds. Gill, S., & Pulido, O. (2007). Glutamate Receptors in Peripheral Tissue: Excitatory Transmission Outside the CNS. Springer Science and Business Media: New York.

Haas, E.M. (2006). Staying Healthy with Nutrition. The Complete Guide to Diet and Nutrition Medicine. Celestial Arts: Berkeley.

Kawai, M., Hirota, M., Uneyama, H. (2012). Umami Taste in Japanese Traditional Miso Soup for the Elderly. Journal of Nutrition and Food.

Kurihara, K. (2015). Umami the fifth basic Taste: History of Studies on Receptor Mechanisms and Role as a food flavor. BioMed Research International. Volume 2015, ID 189402.

Jordon, S. (2005). A Short History of MSG. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture. Volume 5;4 pages 38-49.

eds. Metcalfe, D.D., Sampson, H.A., Simon, R.A. (2011). Food Allergy: Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives. Jorn Wiley & Sons: New York.

Mouritsen, O.G., Williams, L., Bjerregaard, R., Duelund, L. (2012). Seaweeds for Umami flavour in New Nordic Cuisine. Flavour Journal. Volume 1:4. Pages 1-12.

Ninomiya, K. (2015). Science of Umami Taste: Adaptation to Gastronomic Culture. Flavour. Volume 4;13, pages 1-5.

Umami Information Center. (2017). Umami Information by Food; Seafood. (n.d).

Amanda Filipowicz is a certified nutritional practitioner (CNP) with a bachelor in environmental studies (BES) from York University. She also has certification in clinical detoxification, prenatal and postnatal care as well as nutrition for mental health. She has been working as a nutritionist since 2013 and is a lifelong proponent of eating healthy.